Pontius Pilate: The Roman Governor Who Crucified Jesus – His Role in History and the Bible

Introduction

Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Judea during the turbulent first century, played a critical role in the trial and crucifixion of Jesus Christ. Appointed by Emperor Tiberius, Pilate’s governance was characterized by political tension and social unrest among the Jewish population. His controversial actions, such as introducing Roman standards and misusing temple funds, incited protests and violence. In the Gospel of Luke, Pilate is noted for the brutal suppression of dissent, exemplified by his involvement in mixing the blood of Galileans with their sacrifices (Luke 13:1). Despite finding no fault in Jesus, Pilate ultimately capitulated to public pressure, symbolically washing his hands but remaining complicit in the crucifixion. His legacy reflects a complex interplay of power, violence, and moral ambiguity.

Quick Facts about Pilate

1. Pilate was the Roman governor of Judea from AD 26–36. 2. He is known for presiding over the trial of Jesus, condemning him to crucifixion. 3. Pilate symbolically washed his hands to claim innocence in Jesus’ death. 4. He faced political pressure from Jewish leaders during Jesus’ trial. 5. Pilate offered the crowd a choice between Jesus and Barabbas. 6. He received a warning from his wife, who had troubling dreams about Jesus. 7. His tenure was marked by brutal repression of Jewish uprisings. 8. Pilate’s role in Jesus’ crucifixion fulfilled Old Testament prophecy.Pontius Pilate: Navigating Power, Tension, and History

Pontius Pilate might just be one of the most complicated characters in the Bible. We tend to think of him as the guy who handed Jesus over to be crucified, and that’s true. But there’s more to him than that snapshot from the Gospels. Pilate was the Roman governor of Judea, a role that put him at the center of a lot of tension. He wasn’t just dealing with religious issues; he was also trying to maintain Roman order in a land that didn’t really want him there.

“Duccio’s Christ before Pilate (c. 1310) from his Maestà altarpiece in Siena. The painting depicts Jesus standing calmly before the Roman governor Pilate, who is seated on a throne, gesturing with one hand as he addresses the gathered officials and soldiers.

If we dig into the historical context, it’s clear that Pilate served in a turbulent time. Judea wasn’t just another Roman province; it was a powder keg of political, religious, and social unrest. Pilate was appointed by Emperor Tiberius around AD 26, likely due to the influence of the powerful Sejanus, who controlled much of Rome’s administration during that period. Sejanus wasn’t known for his love of the Jews, so Pilate’s appointment came with expectations to keep the people in line, even if it meant using a heavy hand. And Pilate certainly lived up to that reputation.

The Political Pressure Cooker of First-Century Judea

Imagine being the Roman governor in a place where the people see you as a foreign oppressor. The Jews in first-century Palestine were fiercely protective of their religious practices and their sense of national identity. To them, Rome was just another in a long line of empires that had taken away their independence. Pilate’s job was to enforce Roman law and collect taxes while maintaining peace in a place where tension was always just below the surface.

His relationship with the Jewish people got off to a rocky start. Josephus tells us about Pilate introducing Roman standards into Jerusalem that bore images of the emperor (Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 18.55-59). For the Jews, this was more than a political move—it was a religious offense. They saw these images as idolatrous, and protests erupted almost immediately. At first, Pilate ignored them, but the unrest grew so intense that he eventually backed down and removed the images to avoid further conflict.

But this wasn’t the only time Pilate’s decisions fueled tensions. In another account, Pilate took money from the temple treasury to fund the construction of an aqueduct for Jerusalem. While an aqueduct might have been a useful public project, using sacred funds for it was seen as an affront to Jewish sensibilities. The people protested again, and this time Pilate sent soldiers into the crowds, resulting in violence and death (Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 18.60-62). Pilate’s actions consistently demonstrated a lack of understanding—or concern—for the delicate balance required to govern a people with such deep religious convictions.

Munkácsy’s Christ in Front of Pilate portrays a dramatic moment during Jesus’ trial. The painting’s dark tones and detailed figures emphasize the tension and gravity of the scene, capturing the emotional intensity of this pivotal biblical moment.”

Pilate’s Violent Rule and the Gospel of Luke

In the Gospel of Luke, we catch another glimpse of Pilate’s brutal reign. Jesus mentions an event where Pilate “mixed the blood of Galileans with their sacrifices” (Luke 13:1). Though we don’t have many details about this event outside of the Bible, it gives us a sense of the kind of violence Pilate was capable of. This might refer to Pilate’s crackdown on some form of rebellion or disturbance in the temple, but whatever the exact cause, it reflects his willingness to shed blood to maintain control.

Pilate was always walking a tightrope between appeasing Rome and managing the explosive situation in Judea. He knew that any sign of rebellion or disorder could cost him his position—or worse. So when Jesus was brought before him, it wasn’t just a religious issue; it was a potential political problem.

Pilate and the Trial of Jesus

The Gospels give us a detailed account of Pilate’s involvement in Jesus’ trial. In John 18:33-38, Pilate questions Jesus about whether he claims to be the King of the Jews. Pilate seems skeptical that Jesus is any real threat to Rome. In fact, Pilate repeatedly tells the Jewish leaders that he finds no basis for a charge against Jesus (John 19:4). But Pilate is caught between his own judgment and the escalating pressure from the crowd and the Jewish authorities, who frame Jesus as a threat to Roman order by claiming kingship.

In Matthew’s account, Pilate famously washes his hands in front of the crowd, saying, “I am innocent of this man’s blood. It is your responsibility!” (Matthew 27:24). But despite this symbolic act, Pilate still hands Jesus over to be crucified. The truth is, Pilate was no innocent bystander. He had the power to release Jesus, but he chose the path of political expediency. Pilate wasn’t willing to risk his position over a Jewish rabbi from Galilee, no matter how much he might have believed in his innocence.

A Career That Ended in Disgrace

Pilate’s governorship came to an abrupt end around AD 36 after a brutal suppression of a Samaritan uprising. According to Josephus, Pilate’s forces massacred a group of Samaritans who had gathered on Mount Gerizim in search of sacred relics. The Samaritans, incensed by the violence, appealed to the Roman governor of Syria, who in turn sent Pilate back to Rome to answer to Emperor Tiberius. However, by the time Pilate arrived, Tiberius had died, and Pilate disappears from the historical record after that point (Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 18.85-89).

While Pilate’s end is murky, his legacy is undeniable. The Apostles’ Creed even includes him by name, affirming that Jesus “suffered under Pontius Pilate.” His decision to crucify Jesus is perhaps the most consequential moment of his life, yet it’s clear that Pilate’s legacy is far more than just one act. He was a Roman official tasked with maintaining control in one of the most politically charged regions of the empire, and his decisions reflect the complex reality of governing in such a volatile environment.

Pilate’s Historical Reputation

Pilate’s historical reputation varies depending on the source. Jewish historian Josephus and philosopher Philo of Alexandria both present Pilate as a harsh ruler who frequently clashed with the Jewish people. Philo goes so far as to describe Pilate as a man “naturally inflexible, a blend of self-will and relentlessness” (On the Embassy to Gaius, 38). Tacitus, the Roman historian, mentions Pilate in his account of Nero’s persecution of Christians, noting that Jesus “suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus” (Tacitus, Annals, 15.44).

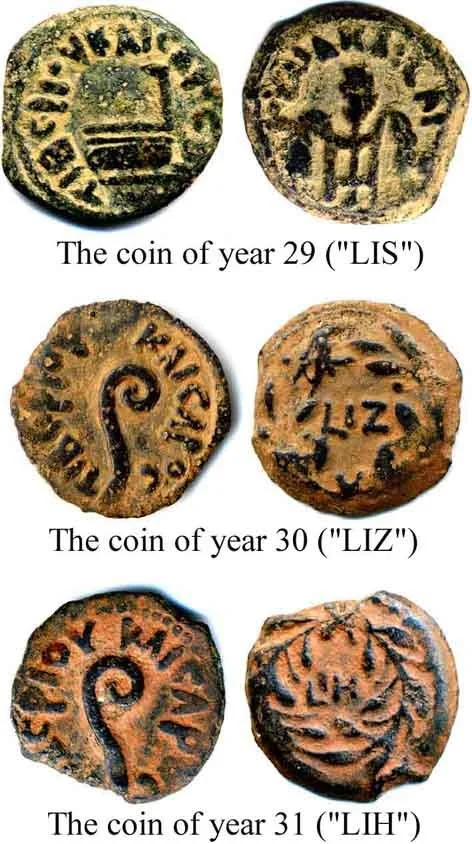

The coins minted under Pontius Pilate, dating from 29-31 CE, feature Roman symbols like the simpulum and lituus. They are significant because they were in circulation during key historical events, including the time of Jesus’ trial. These coins offer a tangible link to Roman rule over Judea during Pilate’s governance.

It’s worth noting that the Gospels portray Pilate with a degree of nuance. While he is the one who authorizes Jesus’ crucifixion, the Gospel writers emphasize his reluctance, especially in contrast to the demands of the Jewish leaders. Scholars like Raymond E. Brown and E. P. Sanders suggest that this nuanced portrayal might reflect early Christian efforts to distance themselves from Jewish authorities while also appealing to Roman audiences. By presenting Pilate as hesitant and somewhat sympathetic to Jesus, the early Christians sought to minimize Roman culpability, thereby reducing tension between Christians and the Roman state. (Brown, Raymond E., The Death of Jesus: Understanding the Last Seven Words from the Cross. New York: Doubleday, 1994; Sanders, E. P., The Historical Figure of Jesus. London: Penguin Books, 1996.)

Pilate and the Bigger Picture

In the end, Pilate’s story is one of power, compromise, and consequence. He governed Judea with the blunt force typical of a Roman governor, and his actions were driven by the need to maintain Roman authority at all costs. But in his decision to condemn Jesus, Pilate became an unwitting participant in a much larger story—one that has echoed through history for two millennia.

For us today, Pilate’s story is a reminder of the complexity of leadership, especially in times of political and social unrest. His legacy invites us to reflect on the consequences of our decisions and the ways in which power can shape history, often in ways we can’t predict.

If you want to dive deeper into the historical and biblical accounts of Pilate, you can check out Josephus’ Antiquities here and read more on Tacitus’ mention of Pilate here. For a scriptural reference to the account of Pilate mixing the blood of Galileans with their sacrifices, you can find it in Luke 13:1.

Pontius Pilate’s story is more than just the backdrop to Jesus’ crucifixion—it’s a lesson in the dangerous mix of politics, power, and responsibility. And in the end, it leaves us asking: What would we have done if we were in Pilate’s sandals?